There are now fourteen Oregon Trail markers in Washington (see comment below), marking  the Oregon Trail cutoff to Puget Sound. In Washington the Oregon Trail followed the Cowlitz River from Fort Vancouver to Cowlitz Landing, then went overland on a rough wagon road to Olympia. There are markers at Vancouver, Woodland, Kalama, Kelso, Toledo, Mary’s Corner, Centralia, Grand Mound, Tenino, Bush Prairie, Tumwater, and Olympia, the end of the trail on south Puget Sound. The trail marker pocket park in Toledo, maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution, Sacajawea Chapter, has been restored and was rededicated in 2016.

the Oregon Trail cutoff to Puget Sound. In Washington the Oregon Trail followed the Cowlitz River from Fort Vancouver to Cowlitz Landing, then went overland on a rough wagon road to Olympia. There are markers at Vancouver, Woodland, Kalama, Kelso, Toledo, Mary’s Corner, Centralia, Grand Mound, Tenino, Bush Prairie, Tumwater, and Olympia, the end of the trail on south Puget Sound. The trail marker pocket park in Toledo, maintained by the Daughters of the American Revolution, Sacajawea Chapter, has been restored and was rededicated in 2016.

Month: September 2016

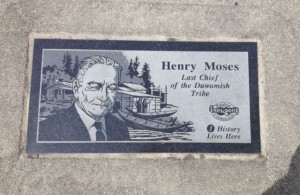

History Lives in Renton

Renton is the 9th largest city in Washington, with a population of more than 100,000. Yet it has been overshadowed by neighboring Seattle and Bellevue, which rank 1st and 5th, and by its association with industry and jobs–coal mining, clay works, Boeing and PACCAR. Even though it has a 405 and Rainier Avenue, the main routes of travel, bypass the main street at a fast clip.

During its centennial in 2001, the city marked a walking tour with markers designed by Doug Kyes with text by Barbara Nilson.  Number one is land where the Duwamish had lived for hundreds of years, at the confluence of the Cedar and Black rivers. The Cedar River still runs through the middle of the city, but only a remnant of the Black River remains after the lowering of Lake Washington in 1916.

Number one is land where the Duwamish had lived for hundreds of years, at the confluence of the Cedar and Black rivers. The Cedar River still runs through the middle of the city, but only a remnant of the Black River remains after the lowering of Lake Washington in 1916.

The community of Renton began when seams of coal were discovered near streams in 1873. A lumberman, Captain William Renton, financed the Renton Coal Company, which opened a mine on the north side of Renton Hill. He was also a trustee of the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad which transported the coal.  The town incorporated in 1901. Located at the south end of Lake Washington along the railroad and a road to Seattle, Renton became a place where Seattle workers lived.

The town incorporated in 1901. Located at the south end of Lake Washington along the railroad and a road to Seattle, Renton became a place where Seattle workers lived.

Renton’s moment of historical significance in Washington, its period of largest growth, was during World War II. The Seattle Railroad Car and Manufacturing Company, which became PACCAR, had moved to Renton in 1907 and produced 30 Sherman tanks a month during the war. The Boeing Airplane Company located a major factory on the north side of Renton and began turning out B-29s at the peak rate of six a day. Thousands of workers flocked to the city seeking work, and the War Department helped build multi-family units. In the decades after the war, Renton became the “Jet Capital of the World.”

The latest new neighbors are the Seattle Seahawks, with a training facility on Lake Washington. Like many cities along Puget Sound, Renton must deal with contaminated properties on its waterfront, particularly the Port Quendall properties where creosote and coal tar were manufactured. The city has enhanced enjoyment of the Cedar River with a walking and biking trail and the city library built over it.

To discover the real downtown of Renton,  follow the “History Lives Here” walking tour, available online or by brochure at the Renton History Museum, 235 Mill Ave. South.

follow the “History Lives Here” walking tour, available online or by brochure at the Renton History Museum, 235 Mill Ave. South.

And does anyone know if there is any historical significance to this mural painted on a building in downtown Renton?

Mount St. Helens

Mount St. Helens remains a stark, startling landscape in the midst of the usually green and heavily timbered Cascades with the clear blue sky reflected in Spirit Lake, the silvered downed trees, the gray behemoth rising above, and a lingering sense of human tragedy haunting the terrain. Yet, it’s coming back. Resilience wins.

When I wrote the chapter in Hiking Washington’s History on Mount St. Helens, I included three trails from the east side since the approach to the west side of the mountain was still blocked by the devastation of the 1980 explosion. In August, 2016, I returned with my hiking group of intrepid women. Much remained the same–the mountain is still gray and fractured, the trees are still down, Spirit Lake is still half-filled with logs–but life is returning.

On the first day we hiked the Boundary Trail on the west side in a perfect storm of unfavorable conditions–a long drive from Seattle, the hottest day of the week (in the 90s), and starting over the exposed landscape at mid-day. Our goal was Harry’s Ridge; we reached the base of the ridge and decided that was enough.

The next day we split up; four of us explored the Truman Trail, which leaves from the Windy Ridge viewpoint and travels south on a gated dirt road, then cuts across the pumice plain at the base of the mountain. The trail is ashy and sandy but broken by creeks and an oasis, providing enough alder shrubbery for a shady lunch. We headed toward Loowit Falls but turned back as clouds came over the ridges and the air turned cooler.

Others in our group took the Harmony Falls trail down to the banks of Spirit Lake, which no longer has signs limiting access.

Then they climbed up to Norway Pass for the most expansive views of the mountain and for close-ups of the wildflowers. At the top of the pass, clouds had obscured the mountain.

The third day some of us went underground, to Ape Cave, then to the dramatic Lava Canyon.

Our fourth day was a cool-down along Siouxon Creek. Wonderful hiking with resilient friends.