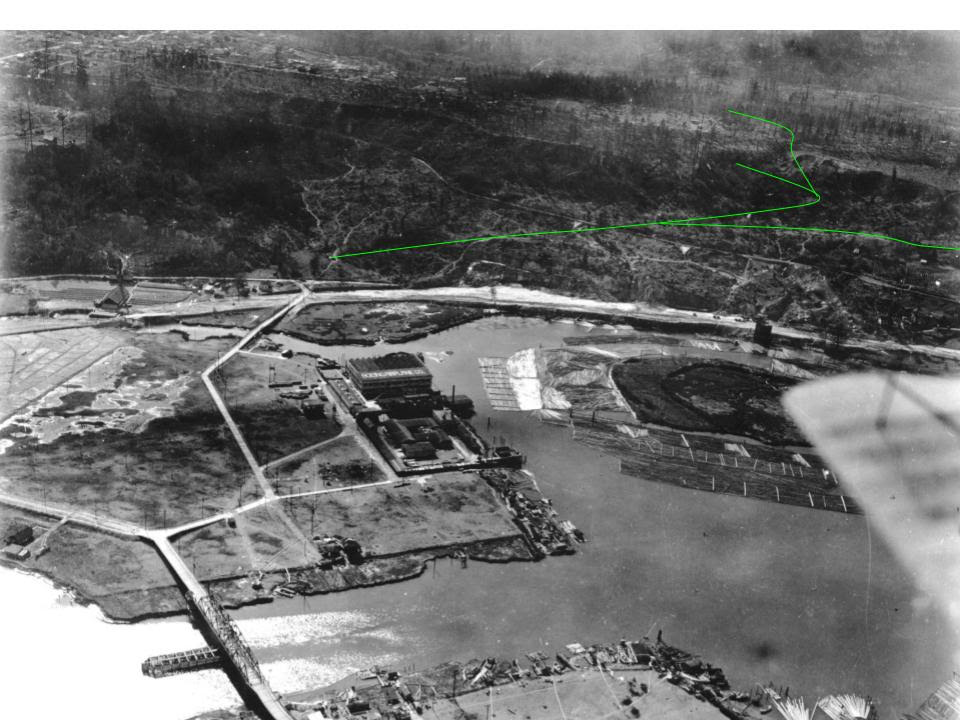

The Coal Mines Trail, which runs from Cle Elum through Roslyn and Ronald, Washington, reflects recent history in its name. After logging, coal-mining was the reason for the towns east of the Cascade Mountains and southeast of Lake Cle Elum. From the late 1880s well into the 20th century, immigrant miners from more than 20 European countries and Black workers brought in from the Midwest worked the rich veins of coal running under the foothills. A memorial of miners who died working and the statue of a miner in front of what was the company store commemorate that history.

But coal mining is a short story compared to the centuries of use by native people. Yakama and Kittitas people have traveled through what is now Roslyn since time immemorial, heading for berry fields in the mountains and salmon fishing on Lake Cle Elum. The summer months of June and July drew large encampments at the south end of the lake, site of a village and large salmon trap. Families camped all along the upper Cle Elum River from Salmon La Sac north to Fish Lake dispersing to gather berries at Paris Creek, Scatter Creek, and Goat Mountain, according to anthropological studies of the area.

Those patterns were disrupted when the Northern Pacific Railway acquired land to not only build a transcontinental railroad but to mine for coal to power the trains. Cheri Marusa, president of the Roslyn Downtown Association, calls native history “the missing truth.” To acknowledge that truth, the Association and the Yakama Nation have funded a new sculpture in Pioneer Park, just feet off the Coal Mines Trail, on the edge of downtown Roslyn. A large metal hand with glass insets in the fingers emerges from the ground on a traditional gathering place.

The sculpture, the Creator’s Law or Na’mi’ Tama’nwit, illustrates five key principles of the covenant the Creator made with the Yakama people:

Cherish the Earth

Cherish water

The Sacred Breath

Everything has a spirit

Connect with ancestors, past and future

The hand rises 14 feet high from a wrist cuff foundation. Glass inserts on the thumb show clouds, Mt. Adams, and the earth from space, illustrating Cherish the Earth. The index finger illustrates water, the giver of life, and each subsequent finger represents another principle. An interpretive plaque at the site gives much more complete descriptions of the art. Three concrete circle benches represent the Witnesses: the sun (A’an), the stars (Sha’ykw), and the moon (A’lxayx).

The hand rises 14 feet high from a wrist cuff foundation. Glass inserts on the thumb show clouds, Mt. Adams, and the earth from space, illustrating Cherish the Earth. The index finger illustrates water, the giver of life, and each subsequent finger represents another principle. An interpretive plaque at the site gives much more complete descriptions of the art. Three concrete circle benches represent the Witnesses: the sun (A’an), the stars (Sha’ykw), and the moon (A’lxayx).

The sculpture was fashioned by Milo White, a metals artist, and Lin McJunkin, a glass artist. They were aided in the interpretation of the principles by several Yakama Nation members, including Chairman Gerald Lewis and cultural consultant Noah Oliver. George Selam, spiritual leader of the Yakama who spoke at the installation in October 2023, stated that the sculpture is an “interpretation of how the tribal members live on a daily basis, following the laws.”

The Creator’s Law acknowledges native heritage but also points a way forward. Estakio Beltran, representing Native Americans in Philanthropy, said “The indigenous knowledge that is contained in this monument has everything we need to chart a path forward.” The goal is to honor continuing land and resource stewardship efforts in the area and to develop educational materials, public displays, and experiential learning opportunities. See the Yakama Nation Footprints brochure on the association’s website for more information, including preservation of a camas field and fish passage facilities.

Trails, too, could be part of that stewardship. Ancient trails led from Lake Kachess and Lake Cle Elum to fisheries and berry gathering areas on the upper Cle Elum River. One primary route, used by leaders such as Ka-mi-akin, Ow-hi, Qual-chan and Quil-ten-enock, led along the river to huckleberry gathering near Salmon La Sac. Large numbers of Indians gathered there at a spear fishing site.

As late as the 1930’s, Indians came through Roslyn on the way to berry fields and fishing, according to Nick Henderson, a Roslyn historian. They camped at Ducktown, a neighborhood in the south part of Roslyn, and soaked wagon wheels in the creek to tighten the spokes before heading over two ridges into Skookum Basin. The old Skookum Road/trail led north from Roslyn over Cle Elum Ridge to the West Fork of the Teanaway River, along the West Fork to Yellow Hill, over Yellow Hill, hooking at the bottom into the Skookum trail at the Middle Fork Teanaway. The trail/road then followed the Middle Fork Teanaway to Skookum Basin.

Today a seldom used and seldom maintained Skookum Basin Trail (1393.2) begins at the Middle Fork Teanaway trailhead (off Forest Road 4305-113) and ends along the Middle Fork/Jolly Creek divide at a high pass. Skookum Basin is likely near the source of the Middle Fork Teanaway below DeRoux and Koppen Mountains, according to Jim Kurseman who authors a website called Hiking Northwest.

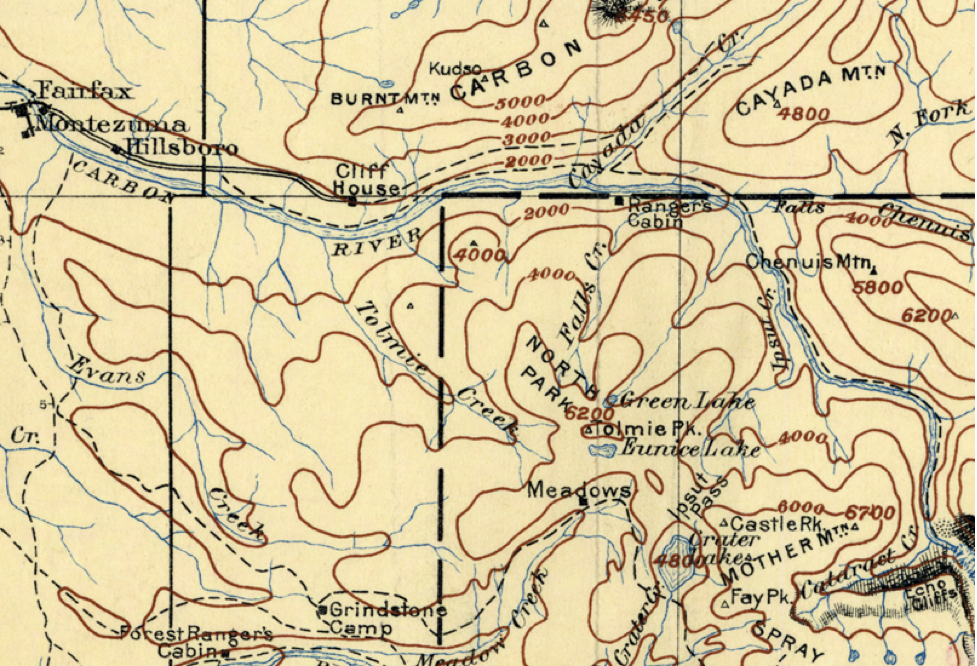

On several maps, “Indian Camp” is sited at the spot where the trail from Roslyn would have reached the Middle Fork Teanaway after crossing Yellow Hill. It’s a plausible camping spot on the way to Skookum Basin. I always trust old names on old maps.