The ghost town of Monte Cristo has come alive again after pollution cleanup. More than 8,000 cubic yards of contaminated material have been removed from the mining boomtown of the 1890s and early 1900s. Two Tuesday Trekker groups combined yesterday to visit the site, an 11-mile round-trip walk with the added drama of a log crossing.

We followed the old mine to market road and the roadbed of the Everett to Monte Cristo Railway into town. The bridge over the South Fork Sauk River has long been washed out, and hikers must wade across at low water in late summer or cross a large tree that has been downed over the river. The log is fairly wide, smooth and dry but narrows at the farther end.

Once at the townsite, we lunched in the basin at the foot of the towering mountains that provided gold and silver to the hopeful prospectors, financiers, and investors.

Since the clean-up of toxic materials (lead, arsenic, copper) that leaked into the soils and creeks, the Monte Cristo Preservation Society has added more interpretive plaques, allowing hikers to roam Dumas Street on a self-guided tour. Alexander Dumas was the author of The Count of Monte Cristo, after whom the town was named.

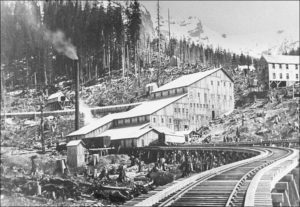

The building called the concentrator climbed the mountainside. Five levels of rollers, washers, and separating tables reduced the ore to “concentrates,” which were then loaded onto rail cars carrying them to the smelter in Everett. The remains of the concentrator are not to be missed.