A hallmark of American progress is our ability to learn from our history.

National Park Service statement on Civil War monuments, August 2017

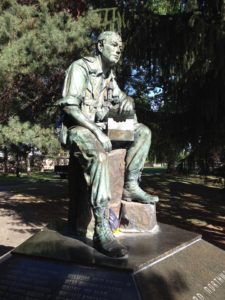

When I was walking cities for Walking Washington’s History, I encountered statues and memorials of all kinds: Chief Seattle and Jimi Hendrix in Seattle, Dirty Dan Harris and J.J. Donovan in Bellingham, William O. Douglas in Yakima, Marcus Whitman and Christopher Columbus in Walla Walla, Henry Jackson in Everett, and Mother Joseph all over the state.  A group of citizens would decide that some person or some event should be honored, convince city leaders their cause was just, raise money and find a suitable public place to make a statement.

A group of citizens would decide that some person or some event should be honored, convince city leaders their cause was just, raise money and find a suitable public place to make a statement.

At the beginning of the 20th century, one such group–the United Daughters of the Confederacy—launched a national campaign to re-interpret the civil war. They wanted to depict it as a war fought to repel invasion and defend states rights, a noble cause, fought by brilliant military leaders and brave foot soldiers.[1] They placed statues of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee on town squares in the South—a reminder to people walking by on the way to the courthouse as to who should be honored and who was in charge. They advocated naming a national highway the Jefferson Davis Highway.

In Washington there had been strong support for the Confederacy both during and after the Civil War. Designating Highway 99 as part of the national Jefferson Davis Highway and the placement of a memorial to Confederate soldiers in Lakeview Cemetery came during a period of renewed segregation and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan in the Pacific Northwest, which targeted blacks, Catholics, Jews, and immigrant groups.

No doubt the soldiers and leaders were brave—they faced horrible deaths and terrible odds. This was truly a civil war, tearing apart the country, state by state, family by family, soldier by soldier. But it was not a noble cause. Alexander Stevens, vice president of the Confederate States of America, made it clear in what was known as his “Cornerstone Speech.” He said the Confederate government rested upon “the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.”

Jefferson Davis claimed that Lincoln’s plan to limit slavery would make “property in slaves so insecure as to be comparatively worthless…thereby annihilating in effect property worth thousands of millions of dollars.”[2]

These issues came to the fore in a program I moderated for the Pacific Northwest Historians Guild: “How Statues and Memorials Interpret our Shared History.” The day before the panel I read an essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates entitled “Why do so few Blacks Study the Civil War?”[3] He described the country’s long search for “a narrative that could reconcile white people with each other.” The narrative we white people have come up with is one of “tragedy, failed compromise, and individual gallantry.”

But blacks see it differently. For Frederick Douglass and for Coates the Civil War was much more important in shaping America than the Revolutionary War. Coates sees the war as “a significant battle in the long war against bondage and for government by the people.” Coates himself has become a frequent visitor to civil war battlefields.

One hundred and fifty years after the civil war, Americans are not free of this conflict. The Guild panel and historian audience argued difficult issues:

- Should offensive statues be completely removed or the plinths retained to remind people what was once there?

- Are memorials on private land different from those in public places? Markers from Highway 99 now stand on private land surrounded by Confederate flags at Jefferson Davis Park, outside Ridgefield, WA.

- Should the ordinary soldier who fights in what others perceive as an unjust war still be honored? Are the Confederate Soldiers monument in Lakeview Cemetery in Seattle, the memorial to Spanish-American war veterans in Walla Walla, the Vietnam veterans memorial in Spokane’s Riverfront Park different from statues of generals?

- Is someone like Isaac Stevens whose treaties with Native Americans were unjust but who died at Chantilly fighting for the Union cause to be honored with street and county names, or is his name to be repressed in the public square? Is he at fault for implementing a policy of the United States government supported by the majority of citizens?

- Can each ethnic group demand its own heroes–Christopher Columbus to Italians, Leif Erickson to Scandinavians?

The most positive thrust to come out of the panel was a look to the future. Who should be remembered? What injustices can be addressed through memorials?

Tacoma has a Chinese Reconciliation Park, remembering the expulsion of the Chinese from the city in 1885. Walla Walla has a new statue of Chief Peo Peo Mox Mox, who was taken hostage and killed during conflicts in 1885. There is a trend toward memorializing the common person, from the Pioneer Mother statue in Vancouver’s town square to Wendy Rose, representative of women welders in the shipyards during World War II.

Tacoma has a Chinese Reconciliation Park, remembering the expulsion of the Chinese from the city in 1885. Walla Walla has a new statue of Chief Peo Peo Mox Mox, who was taken hostage and killed during conflicts in 1885. There is a trend toward memorializing the common person, from the Pioneer Mother statue in Vancouver’s town square to Wendy Rose, representative of women welders in the shipyards during World War II.

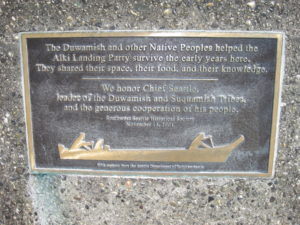

It is also possible to re-interpret old statues. The Alki Landing Monument has added the names of the women of the landing party and acknowledged the role of the Suquamish and Duwamish in helping the group survive. A county named for the slave-holder Rufus King was renamed for Martin Luther King. Jr.

We cannot erase history by removing statues that now offend us. Nor can we excuse ourselves by pigeon holing regional identities. Spokane has a statue of Abraham Lincoln; Seattle has George Washington.

But our heroes and sheroes are not static. We can remove memorials to an unjust cause from places of honor and authority. We can change who we honor in the future.

[1] Erin Blakemore, “The Lost Dream of a Superhighway to Honor the Confederacy,” The Atlantic. 29 August 2017.

[2] Ta-Nehisi Coates. We Were Eight Years in Power, An American Tragedy. One World Publishing, 2017.