Duwamish tribal member James Rasmussen stood six-feet tall in front of my Pacific Northwest History classes at South Seattle College to talk about the history of the Duwamish peninsula, the place we know as West Seattle. He would begin by proudly introducing himself as the son of …, the grandson of…, the great-grandson of …; the great-great grandson of Quio-litza; the great-great-great grandson of Tupt-Aleut and Kruss Kanum–tracing his native line back some 200 years. Giving the names of his elders told knowledgeable listeners what kind of a person he is. I envy that heritage–that he lives on the same land his ancestors lived on for centuries.

As an emigrant to Washington 40 years ago, from Indiana by way of Ohio and New York City, I am among those Americans the Native people describe as restless. I moved away from a homeland that felt confining, especially for women. Like most Scotch-Irish, the McBrides were not landowners until very recent generations. We do not stay put. We must search for resonance—a sense of ourselves in history–in new places. In the United States, we are among the “westering.”

In the book Winter Brothers, beloved Northwest writer Ivan Doig drew a brotherly connection between himself and James Swan, who lived on the Pacific Northwest coast more than a century before Doig. Swan was a mid-1800s jack of all trades around Puget Sound: census taker, customs agent, schoolteacher, Indian agent, amateur anthropologist, and general hanger-on among the Makah and other coastal tribes. He was also a writer who journaled events of his daily life for years. Reading those diaries, Doig found himself “in a community of time as well as of people.” He records watching gulls sail across his line of sight much as Swan saw them a century before him.

“Resonance of this rare sort,” Doig wrote, “we had better learn to prize like breath.”

Another beloved writer, Ruth Kirk, found resonance as she researched and wrote a book on the mudslide at Ozette that buried a Makah coastal village. In work at the archaeological dig, Kirk fingered a piece of basket woven by a woman hundreds of years before her: resonance.

So as I researched and wrote Hiking Washington’s History I searched for resonance on trails, for places where I fit in the community of time and people of Washington.

Finding the contemporary community of people was not hard. Generations of hiker-writers have made trails accessible to newcomers. Louise Marshall started the newsletter that has become the Washington Trails Association’s magazine. She wrote the first local trail guidebook with Harvey Manning and Ira Spring. Jack Nisbet found an historic brother in David Thompson who mapped the 1250-mile length of the Columbia River in 1811. Ruth Ittner introduced me to the Iron Goat Trail. Chuck and Suzanne Hornbuckle led explorations of the Oregon Trail in Washington. Trail advocates Ray and Susan Paolella and Rick McClure, anthropologist for the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, introduced me to the Yakama-Cowlitz Trail.

The community of attentive hikers in Washington is large, but finding the community of people from centuries ago was the surprise.

Looking for historic trails to explore and write about in the state, I found an x on a map of the Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness labeled Indian Corral, so I followed Chief Joseph’s summer trail into the Blue Mountains, to high tableland with only elk and fox for company. I understood why the Nez Perce did not want to leave this land abundant with springs, camas and grazing for horses, stretching for miles into the horizon of mountains.

Standing beneath a sun-shaded petroglyph overlooking the Columbia River, I looked into the face of Tsagigla’lal, She Who Watches. Of course she would watch this river to protect her people from intruders. She still watches.

Seeing young boys dive into the clear, deep water of the Blue Hole at the confluence of the Ohanepecosh River and the Clear Fork of the Cowlitz River, I just knew that people had gathered here for centuries to camp, to fish, to dive into the water. Indeed it is still a campground today, La Wis Wis, in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

Reaching the summit of Cowlitz Pass, with trails leading through meadows and around ponds in all directions, I sensed this was a crossroads, a place where at any moment someone might come around a bend on foot or on horseback. Well-worn campsites along the lakes mark this as a good place to spend summer months, drying huckleberries, hunting elk, among people gathering in the shadow of Mt. Rainier.

There were more places where I experienced the same wonder felt by early travelers and explorers: the blue-green Goblin Gates in the Elwha Valley where Charles Barnes of the Press Expedition imagined a goblin grotto; Yakima Pass where George McClellan felt with his feet that “we had crossed the divide”; finding kinnickinick where the Press Expedition found it, too, in the Olympic Mountains; smelling wild onions on the Umatilla Reservation; hearing the South Fork Stillaguamish River roar over rocks through the Old Robe canyon, a force that frequently washed out the railroad tracks along the side.

But despite these shared experiences, this sometimes felt like a borrowed resonance–not my people, not my place.

I’m from a part of the North American continent with farmhouses surrounded by corn fields and cherry trees. My people came from a different continent, many generations ago. How many generations must one family remain in one place–one county–to feel the same grounding Rasmussen feels? If I went to Ireland and Scotland and Germany and England, would I feel that connection to an ancestral land? I doubt I would find it there, but I might find it in Indiana where I spent most of the first 18 years of my life.

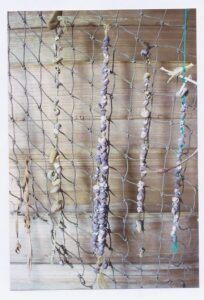

At the same time I was working on Hiking Washington’s History, I was gathering letters my parents had written to each during World War II and fashioning them into a narrative of their young lives in southern Indiana. Both the Hart and McBride families had lived in a few counties there—Daviess and Vigo–originally in a place called “Possum Holler” (Hollow)–for several generations. If I had stayed in Indiana, instead of leaving for college and moving on from there, would I feel resonance in Indiana farmland? Wringing a chicken’s neck like my grandmother did? Canning tomatoes? Unlikely—I spent half of those 18 years in a city, Indianapolis–but I retained the action of snipping the ends off of green beans and rolling out dough for homemade noodles. Both of my grandmothers made quilts—my Grandmother Hart’s unfinished from the 1930s, my Grandmother McBride’s completed in 1970 for my wedding. Sleeping under that quilt is resonance. I feel the soft fabric, recognize some the myriad scraps she fashioned into the wedding ring pattern. I feel her hands, remember her face and her voice. My daughter and grand-daughter have family-made quilts, too: four generations—resonance like Ruth Kirk’s basket.

As my family gathered for my mother’s funeral, in the back of the church I grew up in, an older woman looked at me and said, “You’re a McBride, aren’t you?” The warmth I felt from that recognition may be my equivalent of Rasmussen’s heritage of names