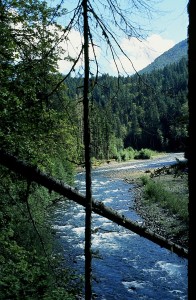

As I was finishing Hiking Washington’s History, I learned about the Lime Kiln Trail, a relatively new trail that follows portions of the old Everett and Monte Cristo Railway grade. The Old Robe Canyon hike in the book follows the South Fork Stillaguamish River on the north bank as the river flows west. The Lime Kiln Trail starts south of the river and joins it after a mile and a half, going east along the south bank of the river to the concrete remains of a bridge that once crossed the river. Engineers warned early on that the force of the river would wash out man-made structures.

Yes, there is a lime kiln on this trail–quite impressive on site.

During the 1800s, the kiln converted limestone into lime (calcium oxide) to make mortar and plaster for construction, including parts of the Everett & Monte Cristo Railway. Limestone from a nearby quarry was carried to the top of the kiln by small cable cars and burned in the kiln to change the rock to powder. Interpretive panels at the trailhead give the history of the railway and the lime kiln. Artifacts along the way (pieces of rotary saw blades, bricks, a bucket) tell a visual story.

This is a 3.5 mile trail, one-way, fairly level (600 some feet of elevation gain, gained in several places) and hikable year-round. (In mid-May 2016 the salmonberries were already ripe.) The first part follows a logging road through regrowing clear cuts but then reaches the old railroad grade and canyon.

Directions: Take State Route 92 east to Granite Falls. In town, turn right on South Granite Avenue. In three blocks, go left on Pioneer Street, which becomes Menzel Lake Road. In a few miles, go left on Waite Mill Road to the signed trailhead on the left.

In late August 2015 I was biking along the Duwamish/Green River Trail and noticed earth-pushers at work across the river where the Carosino farmhouse used to be. The Carosinos were among the Italian truck farmers who first settled along the Duwamish in the late 1800s and eventually raised corn, pumpkins, radishes, and other vegetables to sell at the Pike Place Market. The farmhouse had stood along the path of Sound Transit light rail but survived that construction. Where had it gone?

In late August 2015 I was biking along the Duwamish/Green River Trail and noticed earth-pushers at work across the river where the Carosino farmhouse used to be. The Carosinos were among the Italian truck farmers who first settled along the Duwamish in the late 1800s and eventually raised corn, pumpkins, radishes, and other vegetables to sell at the Pike Place Market. The farmhouse had stood along the path of Sound Transit light rail but survived that construction. Where had it gone?