The Aboveground Railroad

Be ready for briars, flies, and mosquitoes, I was told, and wear good shoes, long pants, and a long-sleeved shirt. I had brought none of these with me to Dorchester County, Maryland, in August, 1988, expecting temperatures in the 90’s—I was not wrong about that. I was writing a young adult biography of Harriet Tubman, who escaped from this county in 1849. I had never been to the Eastern Shore of Chesapeake Bay, a very different world than the Indiana I grew up in and the Pacific Northwest I live in. I wanted to find traces of Tubman in the homeland she lived in and left. I quickly bought jeans, a long-sleeved blouse, and socks to augment my sandals.

My search began on the front porch of the home of Addie Clash Travers, close to downtown Cambridge. Travers was known in the community as the keeper of local Black history. Everyone who went by her house either waved, called out, or stopped to talk. Her family had lived in the county since before the Civil War when many of her ancestors were enslaved. She was in touch with the Rosses, the Pinders, and the Jacksons—other black families who received their names and sometimes land from the oldest white families in Maryland. They wanted to reclaim that 300-year black history that is buried in the white.

Travers learned about Tubman by talking to the “older folks.” The history of slavery was not taught in the schools; it was invisible, underground. “They don’t want to own it, that their forebears were slaveholders,” I was told. It was a troubled history; Tubman, whose family name was Ross, spirited away droves of valuable enslaved people from the county in the 1850s.

Facing official indifference but determined to keep that history alive, Travers started an annual Harriet Tubman Day celebration in 1967, at an old church in the countryside. “It’s hard to believe she did what she did, coming from here,” Addie said, and she wanted it known. Only a few members of her family came the first year.

I wanted to see the church, the farm where Harriet was enslaved, the countryside she knew. Travers walks with a cane, so she could not guide me around, but Herbert Sherwood passed by her porch as we were talking and offered to be a guide. He brought along a last-minute recruit, Monroe William Charles Edward Pinder, otherwise known as Buddy. Buddy was the seventh generation of Pinders in Dorchester County. He traced his height to a Choptank Indian chief, his blue eyes to a white great-grandfather, and his light brown, freckled skin to his black relatives who had lived “the hardest.” Buddy turned out to be a talker.

Our goal was to find the foundations of Harriet’s cabin, which Buddy said he had seen five years before. We started at the only public acknowledgement of Tubman in the county: a lone historical marker which told her escape story escape in two sentences: “Harriet Tubman, 1820-1913. The ‘Moses of Her People,’ Harriet Tubman of the Bucktown District found freedom for herself and some three hundred other slaves whom she led north. In the Civil War she served the Union Army as a nurse, scout, and spy.” The 300 number was closer to 70 as I discovered in further research.

From the marker, we turned down a grass driveway through a field on what used to be the Brodess farm. We alighted into the heat and crossed a ditch, which brings water from the area’s many creeks and rivers. We high stepped over rows of soybean planted after the winter wheat was cut and reach the woods in back. The Brodess house and slave cabins were right up against the Greenbriar Swamp. Locals hunted deer there, for which nearby Bucktown is named.

We didn’t find the foundations of Harriet’s cabin, just some crumbling bricks which Pinder and Sherwood said were brought from England at least a century before. They vowed to come back in the winter when the vegetation would be sparse. If we had kept traipsing through the woods, along the edge of the field, we could have followed the path slaves took to get to Sunday morning worship.As we drove out Greenbriar Road, passing farms and houses, Buddy told me who lived there and whether the family had owned slaves. He pointed out land that was given by Harriet’s owner to his paternal grandmother, one acre for each of the three children she had by him. There was talk of how titles to the land were lost through forgeries or non payment of taxes. His maternal grandmother, he said, was sold to a plantation in Georgia.

We passed the Bucktown store where Harriet was hit in the head with a two-pound weight thrown by an overseer. It was intended for a field worker but hit 15-year-old Harriet who was blocking the door. The injury nearly killed Harriet and left her susceptible to sudden stupors throughout her life, a risk in the underground work she did.

We passed the Bucktown store where Harriet was hit in the head with a two-pound weight thrown by an overseer. It was intended for a field worker but hit 15-year-old Harriet who was blocking the door. The injury nearly killed Harriet and left her susceptible to sudden stupors throughout her life, a risk in the underground work she did.

Down another weedy lane, we found a ramshackle frame house and gravestones dating to 1792. Pinder pointed out The Blackwater Wildlife Refuge, where his grandchildren used to roam before there was an entry fee. We visited Scott’s Chapel on Bucktown Road where the Brodess family were members of the congregation. Harriet’s family, the Rosses, may have worshipped at this site, too, in the balcony or at the back of the church. White burials are behind the church, and the markers of Pinders and others across the road. Early graves of enslaved blacks are unmarked, underneath 20th century vaults and stones.

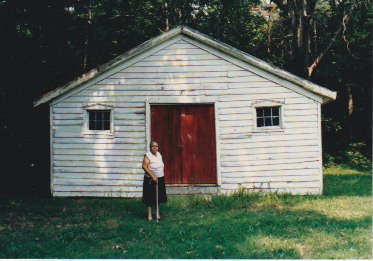

Later, to avoid flies which swarm and bite, I drove with Addie off the road and across weeds to get close to a different one-room frame church. The church was built in 1911 on the site where enslaved peolpe gathered on Sunday morning for worship, walking through the woods from their cabins. Addie had been unable to raise public funds to restore the building, but Sherwood regularly mowed the grass and weeds around it.

The next day I roamed downtown Cambridge, noting small frame houses on Court Lane dating from the early 1800s and the steps of the courthouse from which, I was told, slaves were auctioned. That’s why Harriet left—she had seen two sisters sold to the plantation-cotton factories of the Deep South, and she feared she was next.

This was a history begging to be told but kept alive only in oral history, unacknowledged by the predominant culture. I went on to write and publish the Tubman biography, the first non-fiction account of her life since the 1930s.

Thirty years later, I reprise my trip with the aid of the Internet and feel like Rip Van Winkle. The landscape hasn’t changed, but the attitude has. The underground railroad history in Dorchester County has risen, pushed up by the perseverance of people like Travers, Pinder, Sherwood, and Rev. Edward Jackson and the next generation—Joyce Banks, Sherwood’s daughter; Donald Pinder, Pinder’s son; Rev. Linda Wheatley, also a daughter of a Pinder, John Creighton, a local white historian who did extensive research on Tubman, and James McGowan, who edited The Harriet Tubman Journal in the 1990s. Since my book was published in 1990, three adult biographies have been published. The movie Harriet, filmed in Virginia, brought her story to film in 2019. People are ready not only to acknowledge the conflicted history but to celebrate those who challenged the status quo.

Today Harriet’s legacy and name is everywhere in Dorchester County. Her story is told in a small Harriet Tubman Museum and Educational Center in Cambridge, in a building purchased in 1992 by those determined to keep her history alive. This is not to be confused with the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center, in the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Monument and National Historical Park, a partnership between state and national park services. It was opened in 2017 with a ceremony that included the governor, the lieutenant governor, and a senator from Maryland. The center and garden facing north, the direction of freedom, are based in Church Creek, Maryland, a formerly black community adjacent to the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge. Nearly 100,000 visitors came to the center the first year it was open.

The visitor center is the gateway to the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway, 125 miles of driving to 45 sites significant to Tubman and the Underground Railroad. In 1988 I tried to track Harriet’s journey north from Bucktown on her first trip to freedom in 1849. She followed the Choptank River 67 miles upstream to where it trickles over the Delaware border, then ran a gauntlet of towns. She crossed closely watched bridges to Wilmington, then crossed another state border to Philadelphia, a trip of more than 200 wandering miles when Harriet walked it. Now you can drive it with ease with all the important sites pointed out

The people who first saved African-American history when it was underground have died. Newcomers have moved in and bought the land the locals have been unable to retain. But Bazzle Church now attracts hundreds to the Harriet Tubman Day celebration. The fourth generation proprietors of the Bucktown Store give tours. The same historical marker, with the consistent with every other roadside marker in Maryland, still stands on Greenbriar Road, still claiming 300 fugitives helped. The Brodess farm, now in private hands, is on the scenic byway.

And the foundations of Harriet’s cabin? Slave cabins don’t last; the lives they sheltered lived only in memories through the generations. That community in time has moved on, entrusting the history to interpretive organizations who make it visible and visitors who embrace it.

am working on a new book, a history of Washington told through the history of the state’s major cities. I’m doing a lot of walking, early in the morning when the homeless are still huddled under blankets on benches, on rainy afternoons when awnings are welcome, and sometimes along a sunny waterfront. I am visiting museums, historical societies, libraries, and

am working on a new book, a history of Washington told through the history of the state’s major cities. I’m doing a lot of walking, early in the morning when the homeless are still huddled under blankets on benches, on rainy afternoons when awnings are welcome, and sometimes along a sunny waterfront. I am visiting museums, historical societies, libraries, and coffee shops, talking to anyone I encounter.

coffee shops, talking to anyone I encounter.